Romantisches Brasilien

A romantic aura, with tropical perfumes: this is what Duo Oltheten Gomide demonstrate in these five delightful pieces for violin and piano written by Brazilian composers.

Text by João Marcos Coelho

Instead of applause, you can contribute to our work through a donation:

All-consuming passion, to the point where you become detached from your ego and take on the persona of the object of your admiration. This is how composers, throughout history, have expressed the love they feel for the compositions of others. There are many examples of this admiration in the history of music, regardless of whether their authors knew each other personally. In the 18th century there are two noteworthy examples: Bach and Vivaldi were musically intimate but never met in person nor corresponded and yet the former transcribed and embellished the Italian’s violin concertos for one or more solo harpsichords; the same goes for Haydn and Mozart, in the wonderful exchange of ‘gifts’ in the form of string quartets by Mozart, inspired by Haydn’s works.

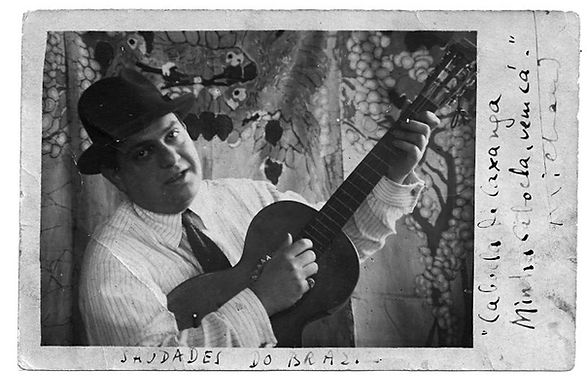

Darius Milhaud (1892-1974) in Brazil in 1917

It was this kind of passion that moved the French composer Darius Milhaud (1892-1974) when he arrived in Rio de Janeiro in February 1917, on the eve of Carnaval, as secretary to Ambassador Paul Claudel. It is generally known that Milhaud loved the popular traditional music from Rio de Janeiro and composed 20th century classics based on it, such as ‘O Boi no Telhado’ (The Ox on the Roof), which caused a stir in 1920's Paris.

Less well-known is his fondness for the music by Glauco Velasquez, a Brazilian composer born in Naples in 1884, who died in 1914, aged only 30. Milhaud devoted his first two months in Rio to studying Glauco's work, and in April 1917 he organised a lecture-concert at the Lycée Français. He performed the ‘Sonata no. 2 for violin and piano’ with Luciano Gallet on piano, followed by the ‘Trio no. 2’ with Alfredo Gomes on cello, unanimously considered one of Glauco's masterpieces.

.png)

The structural problems in the cultural relations that non-European countries maintained with the European musical canon, especially concerning classical music, are demonstrated clearly by one detail. Milhaud delivered his speech in French and, astonishingly, it was also printed in that language in the paper ‘Jornal do Commercio’. French was the language of the educated classes, which set them apart from the rest of the population. Even the avant-garde artist Oswald de Andrade, founded and published a complete publication in this language in 1914. With regard to music, the situation was similar. Here, too, people identified themselves with the Old World until Villa-Lobos revolutionized the Brazilian music scene in the 1920s.

What pleased Milhaud most about Velásquez's music was precisely its European character: deep affinities with romantic European use of language, audacious harmonies and expressive melodic curves. Conductor Lutero Rodrigues, who studied in depth this pre-Villa-Lobos historical period, affirms that “together with Villa-Lobos, Glauco would easily have captured the attention of Brazilian musical circles, had he not died so young”. Milhaud wraps it up: “Glauco belonged to the breed of great musicians”. It's easy to agree with him when we hear the delicate, sophisticated ‘Desio’, (desire) a short piece by Velasquez full of harmonic audacity.

The five Brazilian compositions performed by Henrique Gomide and Daphne Oltheten in these delightful recordings give a sample of the diversity of Brazilian classical music in an era that covers almost half a century, that is between 1880 and 1920. Three of them owe tribute to the great European masters of their time: Carlos Gomes, Henrique Oswald and Velásquez. The other two, Lorenzo Fernández and Luciano Gallet, support the nationalistic musical aesthetics led by the composer Heitor Villa-Lobos and Mário de Andrade (1893-1945). The latter was a critic, poet, musicologist and leading figure in the ‘Semana de Arte Moderna’ (The Week of Modern Art) of 1922, an event that to this day, even a hundred years later, is considered to have been possibly the most important crossroads for Brazilian art and culture.

In his liner notes to a CD recording of two sonatas for violin and piano by Velásquez, the Brazillian composer Martinelli uses the expression ‘tropical Romanticism’ to describe these works. This expression is an apt characterisation that connects the five otherwise disparate compositions performed by the Duo. All of them carry the ambiguity of writing according to European canons and at the same time living in a country that has little - or almost nothing - to do with the Old Continent. We are talking, of course, about the final decades of the 19th century and the first two decades of the 20th century.

Let’s start with Antonio Carlos Gomes (1836-1896), the senior composer in this collection and with Henrique Oswald (1852-1931). Most of the literature written from the Brazilian modernist or tropical perspective - which emphasized musical nationalism – spends a lot of ink trying to define whether or not they deserve to be called Brazilian composers. A distorted perspective, viewed from the rearview mirror of a nationalist vehicle. Carlos Gomes, for example, made his entire career in Italy. In 1870 he triumphed with the opera ‘O Guarani’, whilst living in Europe on a scholarship from the imperial government of Dom Pedro II (at the end of his life, back in Brazil which had become a republic in 1889, he was chased away and humiliated on account of his ties to the monarchy). If you are interested you will be amazed by the chapters dedicated to Carlos Gomes in the books História da Música Brasileira by Bruno Kiefer (Ed. Movimento, 1997) or História da Música no Brasil by Vasco Mariz (Ed. Nova Fronteira, 2000).

.png)

The facts are simple. Carlos Gomes grew up in Brazil, a country which focused solely on Italy where music was concerned. Here opera reigned to such an extent that the greatest Brazilian writer, Machado de Assis (1839-1908), who was also a music critic and even presented himself as a librettist, wrote that “the audience in Rio loves a melody like a monkey loves a banana”. It was only natural that Carlos Gomes focused on writing for the opera. He was an exceptional talent, as demonstrated by ‘O Guarani’ and ‘O Condor’, among others. Gomes’s first opera had its first showing in 1870 in the middle of Giuseppe Verdi's reign, and in the most important and celebrated opera house in the world, the Scala in Milan. ‘Al chiaro di luna’ is an ode to melody, as is his best-known song, ‘Quem Sabe? ‘.

The pianist and piano professor at the Music Department from ECA-USP Eduardo Monteiro dedicated his thesis to Henrique Oswald. He states that “it is inspiring for the researcher to come across the work of a composer such as Henrique Oswald, who, having been highly appreciated and recognised in his lifetime, is nowadays still remembered for matters to which he did not dedicate himself or for what he did not represent”. In other words, our view is obscured by a nationalist interpretation.

_tiff.png)

Born in Rio de Janeiro in 1852, Oswald spent his entire childhood and adolescence in São Paulo, but developed virtually his entire musical career in Europe. He lived there with his mother for many years until he was called to direct the Instituto Nacional de Música in Rio de Janeiro in 1903. Today, historical distance allows us to classify his music as beautiful Brazilian creations embedded in the European romanticism of the second half of the 19th century. His elegant writing, careful framework and typical romantic preference for small forms and miniatures - all this can be heard in the ‘Romanza’ for violin and piano.

Henrique Oswald (1852-1931)

His long life (he lived to be almost 80) gave him a chance to add 20 contrasting years in Brazil to the forty years in Europe. In the 1910s, a visit to his house was a must, not only for local musicians, but also for virtuosos who stopped or performed in Rio de Janeiro, including Rubinstein, Casals, Respighi and, of course, Milhaud.

Two composers who accompanied Oswald for many years and were influenced to some extent by his preference for chamber music were Luciano Gallet (1893-1931) and Oscar Lorenzo Fernández (1897-1948). Unlike him, however, they adhered to nationalist ideals.

Luciano Gallet (1893-1931)

Oscar Lourenzo Fernández (1897-1948)

Vasco Martiz, makes an interesting statement in the book mentioned above: “The Week of Modern Art in 1922 had a decisive effect on the recognition of the merits of nationalistic music which was gradually accepted as modern art. In reality, this music based on folklore had already been highly appreciated in Europe for around fifty years, but distance and post-colonial prejudices delayed its acceptance locally” (p. 111).

The ‘Romance no. 1 for violin and piano’, dedicated to journalist and music critic Benjamin Costallat (1897-1961), was composed in 1918 by Luciano Gallet. He began to study music seriously after advice from Oswald and Velásquez in 1913. Glauco's death the following year touched him deeply. And as early as 1915, Gallet was one of the founders of the Glauco Velásquez Society in Rio de Janeiro, which promoted concerts and publications of scores between 1915 and 1918. His two other idols were Darius Milhaud (with whom he shared a passion for Velásquez's music) and Mário de Andrade (the major influence from that moment on, until his early death in 1931). His ‘Romance’ still shows evidence of its ‘European’ roots, in a manner of speaking.

As for Lorenzo Fernández, he has been wrongly dubbed as a ‘composer-with-only-one-work’, the ‘Batuque’ (the third dance of his suite ‘Reisado do Pasteir’ from 1930), recorded by, to name a few, Toscanini, Koussevitzky and Bernstein with enormous public approval. It is one of the most popular encores, especially with Latin American conductors. In an article on the composer, musicologist Susana Igayara writes that there are still not enough studies “to adequately measure the importance of this composer in Brazilian music history”. He graduated from the Instituto Nacional de Música in 1917. As a first-generation Brazilian with Spanish parents - hence Fernández with an accent mark and a ‘z’ - he completed his entire education in Brazil and never left Latin America during his entire life.

“His work”, wrote Mario de Andrade, “has nothing to do with those ecstatic inventions with which Villa-Lobos frees himself of technique in order to achieve a possible 'technique' justified solely by the beauty of the work” (from the chronicle in ‘Diário de São Paulo’ on January 26, 1934, in the collection of essays titled ‘Música e Jornalismo’ by Paulo Castagna, ed. Hucitec, 1993).

I finish quoting Mário again in the same article. After saying that he uses “the modern improvements of the musical technique of our time”, he concludes that he “is pleased to adapt them safely, when they are logically inevitable, and thus essential”.

This is exactly what we feel when we listen to his composition ‘Nocturnal para violino e piano’, written in 1924, with the three modern opening chords by Henrique Gomide on piano and the violin entry by Daphne Oltheten. An ideal composition to conclude this musical journey, which constantly balances on a tightrope between European roots and a romantic-tropical aura. A practice that the Brazilian Silviano Santiago calls ‘false obedience’ in its best moments: copying from the European but following the tropical canon.

João Marcos Coelho, journalist and music critic, 28th December 2021